This call was published in French by L’Express on December 28, 2024, under the title “Not supporting Boualem Sansal means feeding fear and totalitarianism”.

You can sign it here: https://chng.it/pk9mJc7gkR

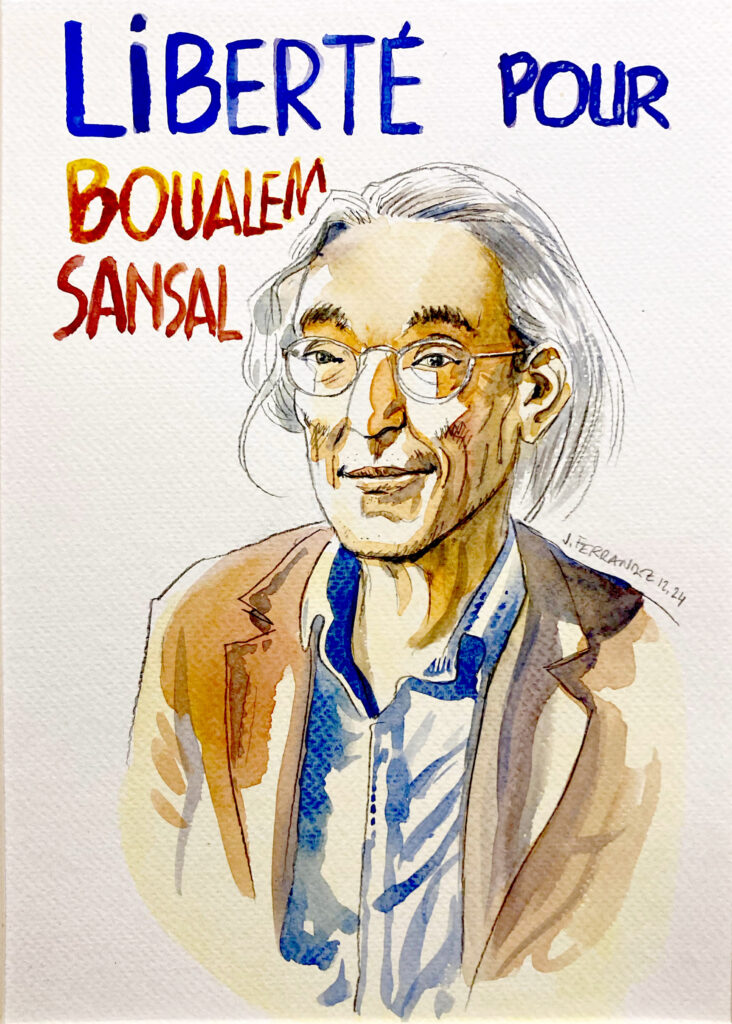

Since 16 November 2024, the French and Algerian writer Boualem Sansal has been imprisoned in Algeria. He is being prosecuted under Article 87 bis of the Penal Code, which punishes “any act targeting state security, territorial integrity, stability, and the normal functioning of institutions as a terrorist or subversive act”—an accusation that could lead to a life sentence.

Boualem Sansal thus adds his name to the many Algerian protesters undergoing repression, abusively detained for simply voicing their opinions or peacefully exercising their freedoms. The Algerian regime imposes a crushing oppression on civil society, reinforcing its authoritarianism at the expense of fundamental rights and freedoms which have been drastically curtailed.

In France, a well-known refrain has been heard with snide critics suggesting that Boualem Sansal is “no angel” due to his supposedly “controversial” stances. As if that could ever justify sending him to jail. As if one needed to “agree” with a political prisoner to support him and demand his release when the essential question is freedom—the freedom to disagree. And anyway, only people who have never read Boualem Sansal’s work could consider him a bigot. As writer and psychoanalyst Boris Cyrulnik recently noted, Boualem Sansal, drawing from his training in sciences, “has chosen to question himself and to question the world.”

Extending that philosophical approach to his own literary commitment, Boualem Sansal does not claim to deliver definitive truths but instead invites everyone, as he himself does in his work, to question their own sets of beliefs. If you’re criticizing Boualem Sansal for his alleged political or historiographical “positions”, you’ve probably never opened one of his books, or too quickly maybe. It is true, though, that since his arrest, too much of the emphasis has been on geopolitical considerations and too little about his actual work.

In his novel Tell Me About Paradise, one of the narrators, Tarik, says: “The reader shall search; that will be his contribution to our redemption. That’s what friend are for after all.” Boualem Sansal envisions the novelistic space he created as a training ground for democratic practice. To make this utopia a real thing, he has always called for the goodwill and assistance of the readers—these “perceptive readers seeking to deepen their knowledge to remain masters of their judgment” (in Gouverner au nom d’Allah); these readers yearning for “genuine debate” without shying away from “the intimidation coming from all sides.” Declaring that “the opinion of the readers carries the weight of law in the joint pursuit of truth” (in Lettre d’amitié, de respect, et de mise en garde aux peuples et nations de la terre), Boualem Sansal invited and encouraged them to pursue his work by contributing their own reflections.

Unfortunately, Boualem Sansal cannot, for now, talk to the readers whom he invited into that circle of dialogue. His silence reminds us of his unbearable absence and unjustified detention, as no authority can suppress the quest for truth and freedom of which Boualem Sansal remains a foremost emblem. Inspired by Boualem Sansal’s works and extending the pathways they trace, we can cultivate a critical vigilance, as readers should towards fiction and as citizens should towards ideologies.

The imprisonment of a writer for his writings hurts everyone’s conscience. Whatever opinion is suppressed, the crime of opinion signifies the replacement of common law by the arbitrary rule of power and partisan preference, disregarding democratic values. This sends a warning to all: a thought police watches, weighing on everyone’s minds. Such a threat aims at silencing any inclination toward critical expression. Imprisoning a writer, then, places a portion of everyone’s liberty under house arrest.

Boualem Sansal is among those free spirits who have chosen to forge a space for collective thought through their work. For this, he is now detained by the Algerian regime, accused of undermining national security for expressing his views. In France, Boualem Sansal is also vilified by some who label him a political adversary while he is imprisoned and silenced, revealing their own conception of debate and coexistence.

Through his very arrest, Boualem Sansal speaks to us of freedom and calls us to extend a hand. Supporting Boualem Sansal is to support democratic plurality, intellectual engagement in public life, the circulation of ideas and literature as a means of dialogue. Failing to support him is to fuel fear and totalitarianism. Failing to support him is to endorse violence and contribute to the intimidation of all. Failing to support him is to silence the spirit of dissidence and protest, threatened both in Algeria and Europe.

Now is not the time for lukewarm reactions or the insidious “yes, but…” We must demand the release of Boualem Sansal because he is showing us that freedom has a price. It is up to each of us to contribute, in words and deeds, by exercising the very freedom that Boualem Sansal has been deprived of. We owe him that much.

We therefore call on all those who still have doubts and those who fear commitment, to hesitate no longer and to rally in support of Boualem Sansal’s release, if only by spreading the word that intelligence should prevail, by reading his books, and by widely encouraging others to do the same. Through his work, Boualem Sansal invites each reader to contribute to the collective creation of a free and open space for debate, based on the ethics of discussion, and to ‘supplement it if necessary by drawing from their own space’ (from Le Train d’Erlingen)—that is, by integrating our own stories, knowledge, sensibilities, and even our disagreements. How could such a suggestion be met with imprisonment, hatred, or indifference? We demand the immediate and unconditional release of Boualem Sansal and all other prisoners of conscience with even greater determination because this is not a call to defend any particular ideas but a call to defend freedom, the foundation of human dignity.

Literature and Freedom (www.litterature-liberte.org)

Authors of the text:

Dr. Lisa Romain, author of a doctoral thesis on the work of Boualem Sansal

Dr. Hubert Heckmann

Pr. Jean Szlamowicz

The first signatories:

Mohamed Aït-Aarab, maître de conférences en littératures francophones

Marc Angenot D Phil & Lit MSRC, Prof. Émérite McGill University

Normand Baillargeon, philosophe et universitaire canadien

Patrick Bazin, Conservateur général des bibliothèques, ancien directeur de la Bpi (Centre Pompidou)

Arnaud Benedetti, rédacteur en chef de la Revue Politique et parlementaire, Professeur associé à l’Université Paris Sorbonne

Georges Bensoussan, historien

Russell A. Berman, professor, Stanford University and Senior Fellow, Hoover Institution

Jean-François Braunstein, philosophe et universitaire

Bruno Chaouat, professeur de littérature française, University of Minnesota

Thierry Chervel, éditeur du magazine en ligne Perlentaucher

Eric Dayre, professeur de littératures comparées à l’ENS Lyon

Anne Fagot-Largeault, professeur émérite au Collège de France, membre de l’Institut

Jacques Ferrandez, auteur de bande dessinée et illustrateur

Christine Goémé, femme de radio

Christian Guemy C215, artiste peintre

Pascale Hassoun, psychanalyste

Danielle Jaeggi, cinéaste

Yves Jouan, poète

Denis Knoepfler, professeur émérite au Collège de France, membre de l’Institut

Michel S. Laronde, professeur émérite d’études françaises et francophones, université de l’Iowa

Pierre Mari, écrivain

Eric Marty, écrivain et universitaire

William Marx, Professeur du Collège de France

Max Milan, écrivain

Gunther Nickel, professeur de littérature, Université de Mayence (Allemagne)

Antonio Augusto Passos Videira, professeur de philosophie à l’Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro (Brésil)

Sabine Prokhoris, philosophe et psychanalyste

Armand de Saint Sauveur, éditeur

George-Elia Sarfati, poète, linguiste, psychanalyste

Pierre-André Taguieff, philosophe et politologue

François Taillandier, écrivain

Claudine Tiercelin, professeur au Collège de France, membre de l’Académie des sciences morales et politiques